Pay Equity: More than an Annual Analysis

By Nanci Hibschman, Amanda Wethington and Michael O'Malley

There are several statistical methods used to examine pay equity. When analyzing compensation, all attempt to achieve the same goal of controlling for group differences. Thus, if the groups are equivalent in all relevant respects, would they (e.g., men and women) be paid the same?

Even when a pay equity analysis comes back citing no statistical differences between groups, organizations must pause to consider if these results reflect a true state of affairs or if inequities are buried deeper within their organizations that an analysis of compensation alone does not reveal. Other fundamental questions need to be asked and answered before the results of a pay equity analysis can be fully embraced as true. We discuss 5 of these questions below, using binary gender norms as our example.

Do men and women separate from the organization at different rates?

If lower-paid women, or those who receive lower counteroffers than men when pursued by competing organizations, exit organizations at a higher rate, then the remaining organizational sample is biased. The sample for the pay equity analysis includes only higher-paid women who have stayed with the organization. Those who have felt unfairly treated have left.

Solution: Test for group differences in organizational exits, examining if compensation is a factor in separations.

Do men and women perform at the same levels?

Equity suggests that those who contribute more should be paid more and vice versa. For example, a woman who performs at a lower level (e.g., is less productive) should be paid less than a man who performs at a higher level and is paid more. The results of a pay equity study will conclude that it is okay. However, if women’s performances are lower than men’s, we must ask, “Why?” Perhaps performance ratings are biased against women, or their true performances are negatively affected by actions that impair performance. For example, women may be provided with fewer resources, developmental opportunities, or mentors.

Solution: Assess performance differences between groups and, where they exist, the reasons for those differences.

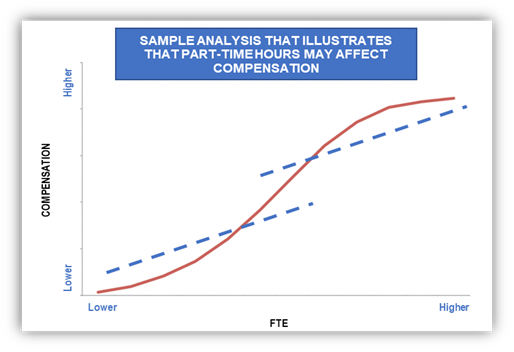

Do women get financially penalized for part-time work?

Many more women than men work part-time (or do not work at all). One reason is that they remain the family’s primary caretaker for the home and children. These facts are reflected in a recent report from the Center for American Progress (The State of Women in the Labor Market in 2023) that shows women’s employment rates are 40% lower than that of men when children under 5 are at home. This gap narrows to 5% when no minors are at home. Additionally, the report indicates that women are 5 to 8 times more likely to have their employment prospects disrupted by caregiver responsibilities through reduced hours or by dropping out of the workforce altogether.

The decision to work part-time may unduly undermine women’s performance and career prospects. For example, part-time workers may be excluded from training opportunities, important meetings, and committees, have less access to critical information and resources, be allotted the most disadvantageous work times, and are often forced to contend with the stigma that they are not serious about their professional lives. Taken together, women working part-time may be at a profound disadvantage, placing their performance and careers at risk for the family’s good.

Solution: Examine the relative incidence of part-time work by group and whether part-time work adversely affects performance and compensation.

Are men and women promoted at the same rates?

In many organizations, the typical financial progression is upward through salary levels. However, that path may be more difficult and time-consuming for women. In this case, women who have faced long periods of stagnation within a job level may receive incremental pay increases that gradually move them higher and higher within their salary ranges. Consequently, they appear to be well compensated for their work. Therefore, women’s pay may aptly reflect their extended tenures by being paid highly within their ranges. However, this obscures that many women may have been passed over for well-deserved promotions and should be at a higher job level and receiving greater compensation.

Solution: Investigate time to promotion by group.

Is the market biased against women?

Differently populated occupations by women sometimes do not get the market recognition these positions are owed: the value of the job to organizations is greater than the market gives credit for. And, yet pay equity studies in the United States are conducted as if the market perfectly assesses value. For example, one function that is immensely complex and central to operational excellence is human resources (70% of chief people officers in Fortune 500 companies are female1 ). There has been ample speculation that the market does not fully recognize the import of this position to organizations. Thus, women paid to the market may be getting less than their true value to the organization, requiring a pay equity analysis that evaluates the worth of jobs independently of the market. While this example is specific to human resources, it applies broadly to other roles held predominantly by women, such as fundraising, programs and teaching.

Solution: In addition to the customary benchmarking of positions, evaluate positions independently of the market using standard job criteria and relate those values to current compensation.

These are a few of the more common questions we suggest that organizations ask and answer. The relief experienced when a pay equity study returns favorable outcomes should only offer partial comfort. A deeper, more inquisitive analysis is required to understand if true equity exists and if it does not, to make meaningful changes so that it can.

[1] https://fortune.com/2023/12/07/women-people-of-color-almost-half-c-suite-locked-out-biggest-jobs/

related Insights